RESEARCH

Asunder archive film stills courtesy of

British Film Institute, Imperial War Museum and North East Film Archive.

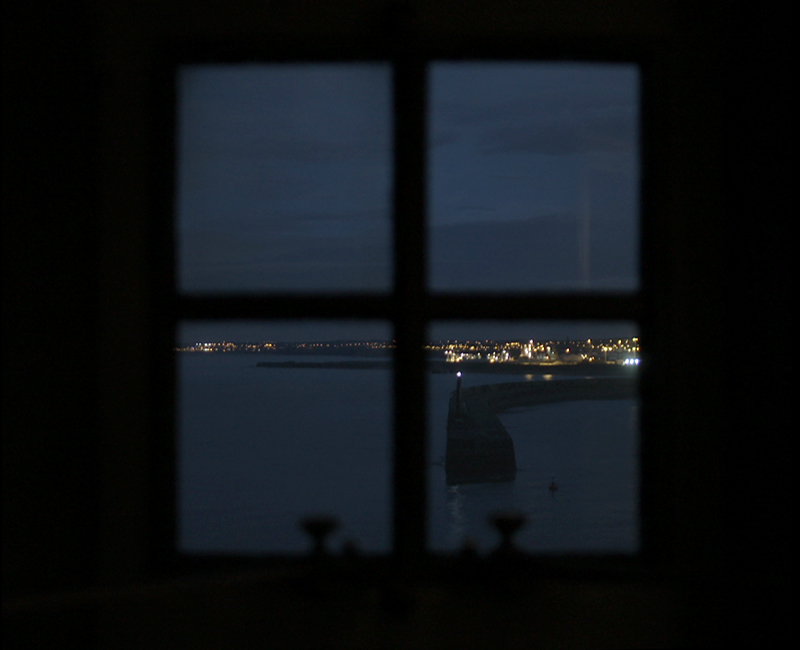

Asunder contemporary footage of Sunderland, North East England, and Richmond Castle in North Yorkshire.

"In making Asunder I wanted to uncover alternative social histories of WW1 – moments of magic during the horror, attempts at finding normality in abnormal circumstances – to find a new way of understanding the war and give prominence to stories that may not have been given space in the history books.

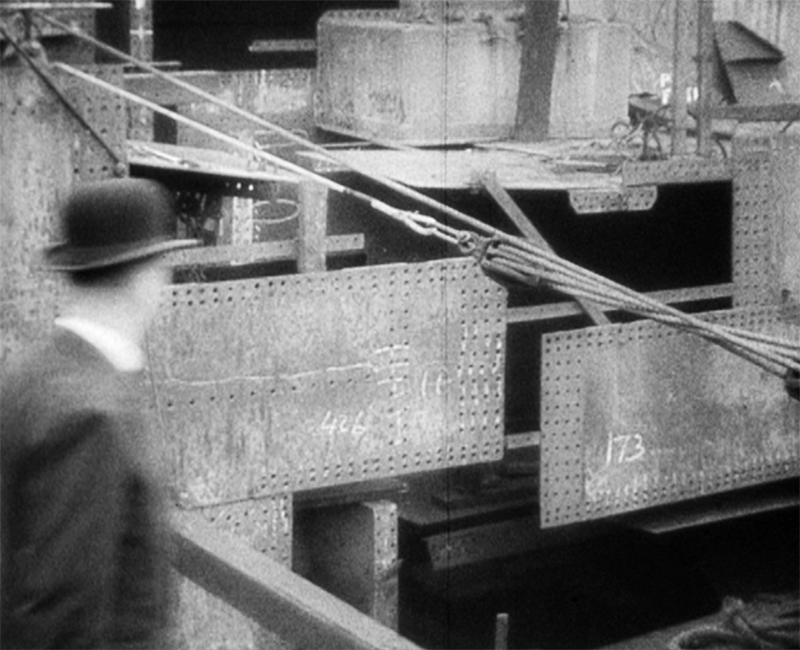

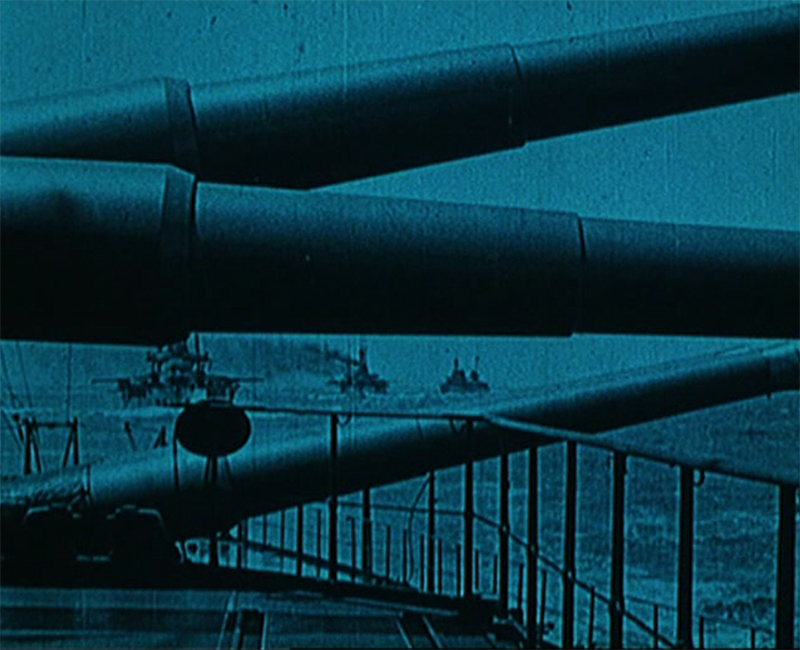

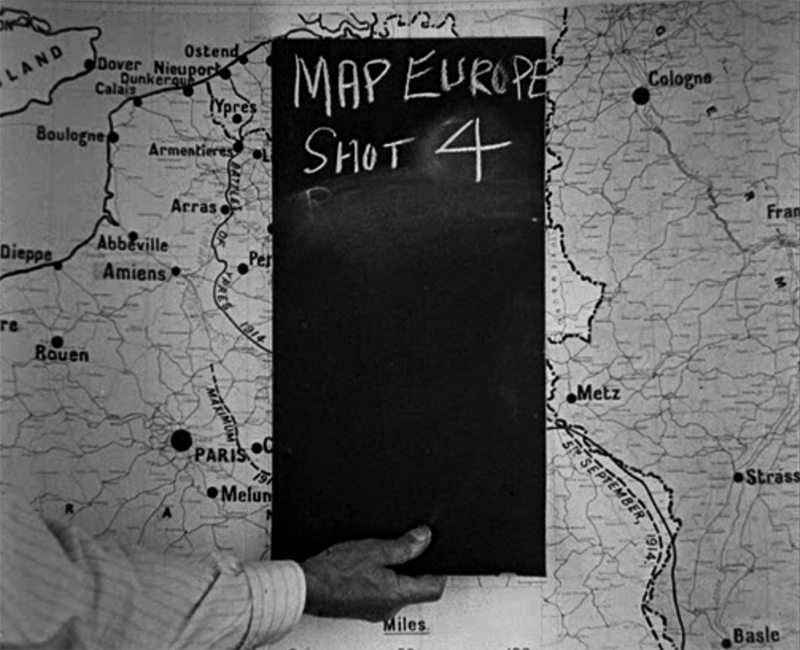

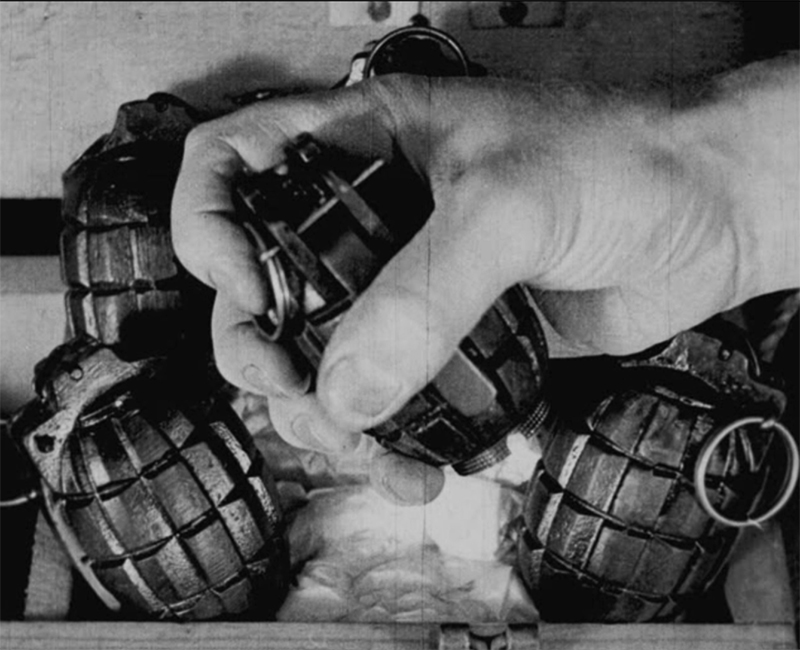

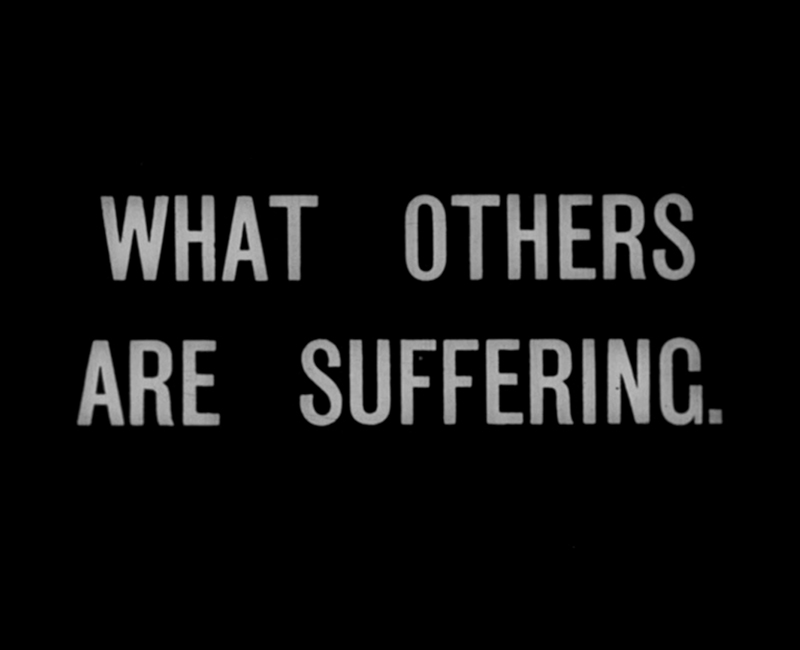

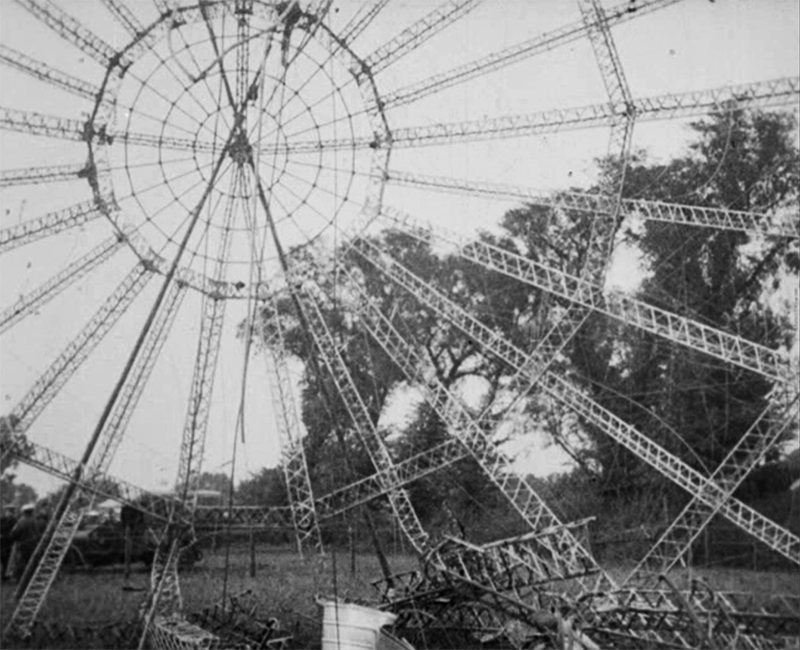

In researching rarely seen archival film I was keen to find footage of WW1 that you might not expect – shots that clearly show the friendships forged between young soldiers; animations of zeppelins, a man-in-the-moon, and ships at sea; a soldier attempting to kiss a girl under the Christmas mistletoe; graphics and inter-titles; and footage from a different point-of-view, be it taken from the front of a tank, or from an airship. Archive material is mixed with contemporary footage of locations in Tyne and Wear as they exist now in order to bring the period of 1914–18 to life in sometimes surprising ways. Contemporary footage is themed into sections of Home, Leisure, and Work.

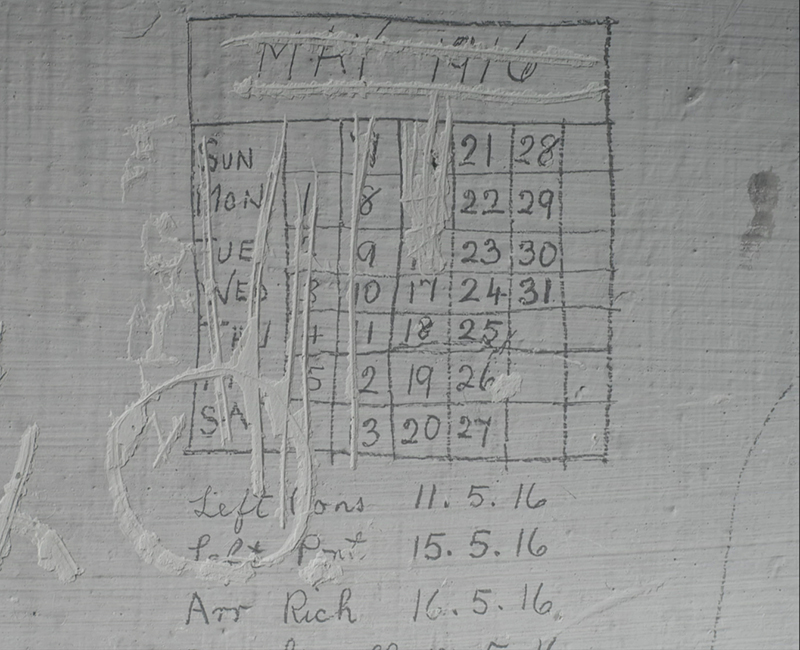

Further research was undertaken in local and national archives with a focus on drawings, letters, diaries written during the war, and memoirs and oral history recordings from survivors reflecting back on the war. The film narrative has been woven from this material, in addition to articles published in 1914–18 copies of the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. We were lucky enough to have Kate Adie and Alun Armstrong narrate the film, both from the North-East and familiar with locations where individuals featured in storyline’s had lived.

I was fortunate to be able to track down living relatives of some of the individuals featured in the film. This dialogue presented a further personal perspective of people’s histories and the legacy of the past on specific families. Some relatives have written texts about their family members for me and these texts are included below.”

– Esther Johnson, Director of Asunder

A Q&A with Esther Johnson, hosted by director of Birds' Eye View Film Mia Bays, is available HERE.

CC (Closed Captions) for deaf and hard of hearing can be switched on for the Q&A.

people’s histories

Asunder consists of stories from the

HOME FRONT

· NORMAN GAUDIE (1887-1955)

a conscientious objector, devout Quaker and Sunderland AFC centre-forward. Norman’s son, Martin Gaudie, was a conscientious objector in WWII.

· LIZZIE HOLMES (1893-1979)

the first woman in Horden, County Durham, to wear trousers. Lizzie got a job in a ropery in Hebburn at the age of 13, and at 14 she had the name of her sweetheart ‘Jimmy Holmes’ tattooed on her arm. They got married in 1913 and when Jimmy went to war, Lizzie got herself a job in the coke ovens in Horden. She joined a women’s football team whilst working in Horden.

· MARGARET ANN HOLMES (1895-1986)

a tram conductress who survived a Zeppelin air raid oin Sunderland on 1 April 1916 when she was 21. 22 people were killed in the attack and over 100 injured. Margaret suffered from substantial injuries from the raid and fought for compensation.

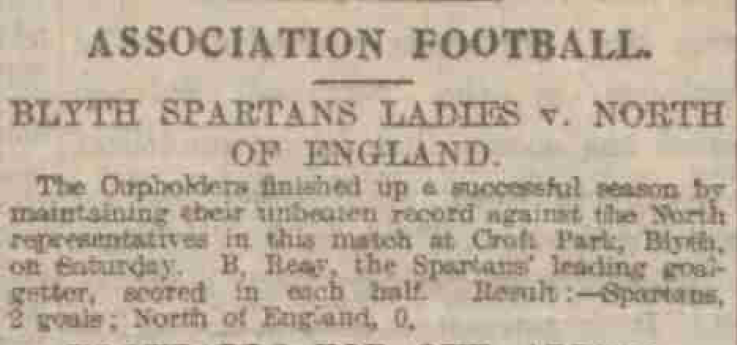

· BELLA REAY (1899-c.1970s)

a young munitions worker and whizz footballer scoring 133 goals in one season. The FA banned Women’s football from its grounds in 1921, and it wasn’t until 1969 that The Women’s FA was formed.

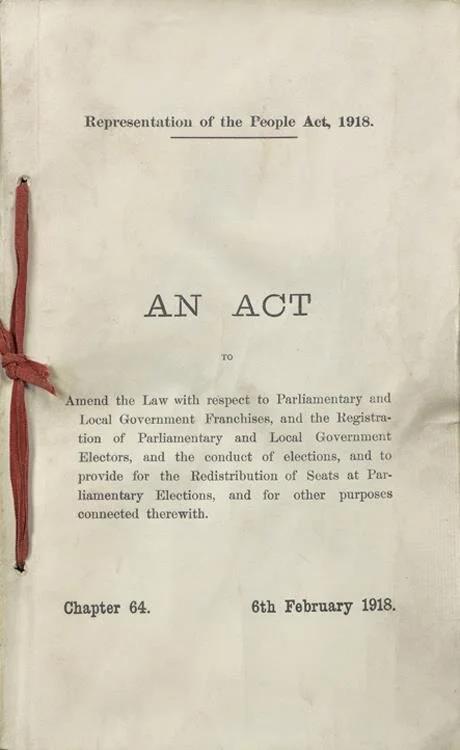

· LISBETH SIMM (1870-1952)

was a member of the ‘Women’s Labour League’ and a devoted working-class campaigner for women’s rights. She tirelessly spoke at countless rallies about women’s rights injustices, and wrote, “The life of the working woman! No, you cannot understand it unless you’ve lived it!” “One of the most serious problems of our time is that of life on an insufficient wage.”

Collaged with stories of the

WESTERN FRONT

· ROBERT HOPE (1898 -1917)

(AKA James Hepple)

at a 19 years old, Robert was soldier — one of the 306 soldiers in WW1 shot at dawn for desertion as he went AWOL for 11 weeks on the front. Prior to the war Robert worked in the shipyards in Deptford, Sunderland.

· Capt. ALAN LENDRUM (1887 -1920)

refused to kill Robert Hope on account of him knowing the man. Alan was court-martialled for refusing to take charge of the soldier’s execution, and as a consequence was demoted from Captain to Lieutenant. He won the Military Cross and was wounded five times during the war.

· ARTHUR LINFOOT (1881-1975)

a soldier in the non-combatant Royal Army Medical Corps who spoke German and didn’t agree with killing. Arthur kept a diary between 1914-18, which was published in 2019.

· GEORGE THOMPSON (1893-1958)

loved his horses and became a Sergeant transport driver taking ammunition and rations to the front line. George’s story mirrors elements of ‘War Horse’ as he brought two horses to France from Sunderland and one of them survived until the end of the war. He worked at Vaux Brewery in Sunderland on his return from the war.

· GARNET WOLSELEY FYFE (1879-1916)

a Lance Corporal and piper killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, whilst going ‘over the top’ playing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’.

Norman Gaudie

norman gaudie

“After the war when Norman came home he found that no one wanted to employ him and he was rejected by the East Bolden cricket club where he had been a valuable player before the war. The Miners team was very pleased to have him join them and they had the best season ever. He also started to attend Newcastle Quaker Meeting where he became a member and it was through that he met his wife, Eva Briggs. At the time Eva was looking after Austrian refugees in the glass houses at Wheelbirks farm, the home of Hugh Richardson, and this delayed his marriage. He eventually found work as a salesman but Martyn Pumphrey, a Quaker, offered him employment as a secretary at the Pumphrey sugar mill in Thornaby and he and Eva moved to Nunthorpe. Soon after the move their son Martyn was born. Sadly Eva died in childbirth from haemorrhage so now Norman was left with the responsibility of a baby to look after.

His sister Elsie stayed for 6 months then Eva’s sister Louis came for 6 months and Martyn slept with his father. This routine lasted for 8 years when Norman married Ruth Pumphrey.

Suddenly Martyn had to sleep on his own and go from being a vegetarian to eating meat.

Norman continued to play cricket at Normanby Hall cricket club which is where Norman’s great grandson now plays. He also played the cello for a local orchestra.

Norman sadly suffered from asthma as a result of the bad conditions at Dice camp near Aberdeen and this is what he died of. He wrote an article for The Friend entitled “The courage that brings Peace “ which gives some small idea of what they had to endure [quoted in ‘Asunder’].

My husband Martyn Gaudie became a CO during the Second World War and was given farming as an alternative to fighting — his father and others like him having paved the way for an alternative to fighting being possible. I feel very proud and privileged to be a part of this family and what they stood for.”

— Marjorie Gaudie, daughter-in-law of Norman Gaudie

Pencil drawing of Norman Gaudie's mother in a cell at Richmond Castle, North Yorkshire where Norman was imprisoned during the war

Norman Gaudie after the war

Norman (centre) and friends

Sunderland Association Football Club grounds where Norman was a team member before the war

Norman Gaudie after the war

Lizzie Holmes workplace Koppers Coke Ovens in Horden

lizzie holmes

“Mother worked at white lead factory and got parish relief. Joined sisters working in ropery, only 12. Hit a boy, nearly got the sack. Hard work making washing lines. With early wages, got a barrow full of tarry wood and sold it door to door; left ropery to do this. Moved around between different relatives, got married at 18. When first world war started, got work building coke ovens, labouring, pay and conditions, became strong. Husband lost his war pension because wouldn't go for a medical, never put himself forward for things. Equipment and methods constructing coke ovens. Husband used to try to not go back to war, when he got leave. Going to dances, would “clip” (hit) another woman who bumped you, afraid she’d killed one. Did housework for various people. Also ran buses for groups of people on day trips. Got tattoo of boy she liked, while still at school, with group of friends, one wrongly spelled; pretending she had another. Had to pull sleeves down to hide it while in service uniform. Father would pull out aching teeth with a door and bobbin. He also ripped her earring out, but she had it redone. Once had to show her tattoos to an audience on holiday. Involved in Horden Carnivals, first one 1915, different characters and floats. Played in women’s football team for the coke ovens. Husband turned her boots and shorts into pit boots and hoggers so he could go down the mine on his return from the war. Got uniform for ovens – went to post a letter and everyone stared, first woman in Horden in trousers! Worked as a team, left and right handers. Double possing as a child. Gave up two houses for a very big colliery house, large family; later swapped back for two so daughter’s family got one – trouble because didn’t tell husband first. During the way, looking after a lad from the orphanage, who went to woman who didn’t feed him, so he wouldn't get the sack – but told had to go to a Catholic family. Woman had quins, but they died. Own mother had triplets that died, got a guinea from the Queen for the birth.”

— Oral history with Mrs Holmes held in the Beamish Collection

Describing herself as ‘rough and ready me’, Holmes was renowned for being the first woman to be seen wearing a pair of trousers in Horden, a village in County Durham. Holmes was an orphan and was moved around between different relatives. Before she reached thirteen, when she was legally allowed to leave school, she was already in search of a job. Her elder sisters worked at the ropery in Hebburn, where, at the age of twelve, Holmes managed to find a job which she subsequently lost for beating up a bigger and older boy. Holmes found a job in the Koppers coke oven at Horden when her husband went off to war. Here, she continued to challenge the conventions of the day. She joined the women’s football team and wore a uniform whilst working in the cokes oven. One day, when she went to post a letter, everyone stared and cried out, ‘first woman in Horden in trousers!’ In an interview, Holmes described children gathering around her to prevent her from going home. The next day, other married women in the village put on the same clothes and went to work with her.

http://www.durhamatwar.org.uk/story/11203

Margaret in her tram conductress uniform

margaret

ann holmes

Tram (fleet no 10) at the Wheatsheaf Depot was destroyed by a Zeppelin air raid in Sunderland on 1 April 2016. The "Rules" stated that staff had to stay with the tram during an air raid. An Inspector was killed and conductress Margaret Ann Holmes received a bad injury to her leg and. Miss Holmes returned to work in the Tramway Offices after months in hospital. She retired in 1950 and died 1986 aged 91.

The zeppelin crew seem to have had a good knowledge of the area. They went for collieries and the colliery power station at Philadephia which are almost in a straight line as the crow (or airship) flies. The tram depot was very close to Wearmouth Colliery. Any bomb dropped would have hit something important.

The tram Margaret was conductress of after a zeppelin hit on 1 April 2016

Bella Reay c.1916

bella reay

Thousands of women munition workers played football during World War One but one team in the North-East stood head and shoulders above the others.

Blyth Spartans Ladies FC had been taught to play by navy lads on the beach and in two years they were never beaten. Their centre forward Bella Reay scored 133 goals in one season and went on to play for England.

In 1918, a knock-out competition called the Munitionettes Cup was held which attracted 30 teams. Blyth Spartans were the eventual winners, beating Bolckow-Vaughan of Middlesbrough at Ayresome Park in front of a crowd of 22,000, Bella Reay getting another hat-trick.

The women were highly skilled and competitive but when the war ended the factories closed and their teams folded.

A few of the women continued to play, but in 1921 the FA banned women’s football at their grounds bringing an end to a colourful chapter in women’s sport, which has long been overlooked.

Blyth Spartans in 1918 with Bella centre front

Blyth Spartans and Bella centre front with cup

Blyth Spartans with Bella centre front

Bella scoring a goal

Jack and Bella Reay

lisbeth simm

“Lisbeth was my great grandmother. I grew up in Liverpool New York which is where Lisbeth first came when she left England. She lived with my father when he was a young boy for a short time. She later moved to California. As a child I was told how Lisbeth had helped set up women’s [she was a member of the Women’s Labour League] and children’s rights, and also the Labour Party and the support of coal miners in the North of England. I was also told that after the war she travelled the world trying to help women find jobs once the men returned. I once had a box [recently stolen] containing opals from her visit to Australia and gold covered beetles from India.

I have a memory of an anecdotal story of when my great grandfather was up for running the second time for Parliament that the Labour Party approached Lisbeth to run instead. That sounds like a very family story that may or may not have been true at all. However, it does make me smile. Unfortunately my great grandfather lost by a landslide in the second round.

Even though I never met her, I think of Lisbeth as a role model for me. Her passion and commitment to her cause are inspirational. I speak about her frequently to friends and coworkers and believe a lot of my personality has been inherited from her. It is wonderful her story is included in ASUNDER.”

— Kendra Simm, great-granddaughter of Lisbeth Simm

Robert Hope’s [AKA James Hepple] grave in Ferme Olivier Cemetery Ypres which Esther visited for a centenary service to commemorate his death

robert hope

“It’s hard to talk about a family member who because of tragic circumstances I never met. Sad that nobody in the family talked about him, not through shame I guess but more that his move to Ireland and his change of name seemed to be responsible for his break of contact with his Sunderland family. I feel that after his previous good conduct his ‘desertion’ was due to a nervous breakdown, something not really recognised at the time. He is certainly not a coward in my opinion as I think any soldier involved in the dreadful conditions of World War I was a very brave man.”

— Bernard Hope, second cousin of Robert Hope [AKA James Hepple]

Ferme Olivier Cemetery, Ypres, 5 July 2017

Centenary commemorative service for Robert Hope at Ferme Olivier Cemetery, Ypres, 5 July 2017

captain alan lendrum

“I owe my interest in the First World War to my Great Uncle, Captain Alan Lendrum whose incredible story continues to resonate. I grew up in the Northern Ireland 'troubles'. His grave was in the local church and there was a vague story that he'd come to a sticky end. There were whispers that he was the one that got 'buried in the sand'. It took a few years for that tall story to unravel, but its taken me on some incredible adventures, meeting some wonderful people, forming life-long friendships. His medals were on display in the local museum but his mysterious death in an IRA ambush in County Clare seemed to overshadow an extraordinary life. The youthful sailor boy who circumnavigated the globe. The adventurous colonial who planted rubber in 'Malaya'. The eager recruit who joined the war effort in West Africa. A decorated hero who won an MC for organising the wire in the attack at Tunnel Trench in 1917. A gaunt, bowed figure by its end, yet still he came back for more. Off to Russia in 1919 to fight Bolshevism, to revolutionary Ireland in 1920 to take up a dangerous position of Resident Magistrate. An old scrapbook in the family home put together by his mother provides clues to his life and among it a few pieces of paper which lead us to the story of his involvement in the execution of a fellow soldier in the Inniskilling Fusiliers. But he wasn't actually involved. He refused to follow that order and was subsequently courtmartialled. Letters and accounts by his men indicate he was a good man, kind and generous, brave to a fault. But now I liked the sound of him even more. More adventures lead me to Belgium and the grave of Robert Hope in Ferme Olivier. The story of the teenage ‘Tommy’ from Sunderland and his young Derry bride is worthy of a film in itself.

I was so proud a few years later to discover that Esther Johnson had woven the narrative of Robert into her ASUNDER film and mentioned my Great Uncle. Seeing it on screen for the first time in London and knowing the story would be preserved forever was extraordinarily moving. A few months before that, another unforgettable moment beneath the blazing Belgian sun in Ferme Olivier on 5th July 2017. Standing with Esther and her Dad, we joined VIFF (The Friends of Flanders Field Museum) in a ceremony by Robert's grave, exactly one hundred years after his death.”

— Geoff Simmons, Nephew of Captain Alan Lendrum

Captain Alan Lendrum

Geoff Simmons at the grave of Robert Hope

Ferme Olivier Cemetery, Ypres

Arthur Linfoot

arthur linfoot

“My father Arthur Linfoot would have been very pleased and proud if he could have known that he would figure in ‘Asunder’,

a feature film about Wearside. He never sought publicity, and on the very rare occasions when he was briefly mentioned in the Sunderland Echo or seen on local TV, he seemed to feel that it was bizarre that it could happen to him. He would certainly have been glad to be featured so sympathetically among the many other people and aspects of Wearside’s life and work in WW1, into which the film gives such insights.

In his Diaries covering World War 1, which he kept without any thought that others would read them and which are thus free from any suggestion of posing before an audience, he makes no claim to heroism, but – for example – on the eighth day into the Somme (8 July 1916) – he writes “Everybody tired out . . I thought I was going to drop first thing . .” but later in the day, when his Captain asked for volunteers “to bring in a few more men”, he writes simply “I volunteered.” Fifteen days later (a Sunday) he tells how a shell 6 feet away blew in the side of the trench and buried two comrades, and he writes “A machine gun played over us the whole time and we had to dig them out with our hands. Like a nightmare.” But in spite of suggestions that he should publish his diary, he never thought it worth doing so.

But I think he would have been particularly pleased that the ‘Asunder’ film makes it so clear that however difficult the decision was, he felt it was the Royal Army Medical Corps which he must join. Much later in his life he strongly emphasised his abhorrence of the slaughter, and I too am grateful that ‘Asunder’ does this justice to his beliefs.”

— Denis Linfoot, son of Arthur Linfoot

Arthur in his RAMC uniform

Arthur Linfoot’s original diaries

Arthur’s diaries published in 2019

george thompson

In October 1910, shortly before his seventeeth birthday, George joined the Territorial Force. This was a part-time army, the forerunner of today’s T.A. Among his papers there is a photograph of him at the DLI Territorials’ annual training camp at Conway in North Wales in July 1914, only days before war broke out. He was there a week before the battalion was called back home as England had declared war on Germany.

George was ‘picked for a transport driver’. In 1914 motor vehicles were expensive and not suited to travelling over muddy or rutted ground, and so the ‘transport’ was horses and carts. George spent several months training in Gateshead and the grounds of Ravensworth Castle, learning how to ride bare back and with a saddle and how to drive heavy wagons.

After eight months George set off with the 7th Battalion for France in April 1915. The horses and drivers of the transport section left Gateshead station two days ahead of the rest of the battalion to allow time to stop and feed the horses en route. At Southampton the battalion boarded the SS Dunkirk and sailed overnight to Le Havre.

For George Thompson this was the start of almost four years of war service, driving rations and supplies to where they were most needed, often under enemy fire. George described his experiences in a compelling memoir written in 1928.

http://www.durhamatwar.org.uk/story/11354/

George with his beloved horses

George Thompson diary extract

George Thompson is stood on the left

Rachel and Garnet Fyfe with son Ronald

garnet

wolseley fyfe

“My grandfather Garnet Wolseley Fyfe was born 16th August 1879 in Edinburgh. He was the son of James and Agnes Fyfe and was the sixth of seven children. The family moved to Backworth in Northumberland about 1900. All of the men of the family, including Garnet, were coal miners. In June 1906 he married Rachel Burrows and in May 1910 my father, Ronald was born.

Garnet joined the 23rd Tyneside Scottish Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers. He was a Lance Corporal Piper, his service number 20/237, and along with his regiment was sent to the Somme. On July 1st 1916 he was killed as he piped his fellow soldiers into battle. He is buried in Ovillers Military Cemetery in Northern France. Garnet’s dirk was recovered from his body and is now in private ownership.”

— Diana James, granddaughter of Garnet Wolseley Fyfe

Garnet in his Scottish Tartan with ceremonial dirk

Garnet’s dirk is now in private ownership

![Robert Hope’s [AKA James Hepple] grave in Ferme Olivier Cemetery Ypres which Esther visited for a centenary service to commemorate his death](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577121a9e58c62d50f9f2c26/1581973791927-A83C3SHIXF576O2ZC1L3/Robert+Hope+grave+in+Ferme+Olivier+Cemetery+Ypres+%C2%A9+Esther+Johnson+2017)